Contraband comes in different shapes and sizes and down on the border, between Texas and Mexico – a porous and narrow crossing over the barely flowing Rio Grande – there’s plenty of opportunity for it to be transported, whether of the human or pharmaceutical kind.

Trafficking desperate people from all over South America, backpacking marijuana or methamphetamine by shallow steps or dashing across the water in a 4 x 4 with a cargo of heroin or cocaine – these are the industries that thrive here, feeding off the hopes and dreams of the poor folk, who either live in or have travelled up to the Northern Mexican region of Chihuahua, seeking a new life over the “Big River”.

“Contrabando” – there’s even a movie set by that name – a ghost town that became the setting for the Roy Clark film “Uphill all the Way”, when it was constructed in 1985, as we found after taking the 80-mile run down from Alpine to Terlingua then heading west on the old Farm Road through Big Bend Ranch State Park.

Located 9.5 miles west of Lajitas and consisting of an original adobe building called ‘La Casita’, with several later additions, the Contrabando site has been used as a set for nine other movies including John Sayles’s “Lone Star” of 1996 and “Dead Man’s Walk” and “Streets of Laredo”, which were part of the “Lonesome Dove” mini-series, based on a novel by Larry McMurtry. In September 2008, heavy rains over the border in Ojinaga and the ensuing release of water from local inundation control structures, caused widespread flooding resulting in damage to the movie set. But it’s still there today, a tourist attraction perched precariously on the edge of the river.

However, the real action down here at the frontier is not of the movie-making kind but, rather, it’s the constant struggle by Border Control to chase down and apprehend the human mules and cartel-organised incursions into sovereign US territory that are the order of every day and night.

The Big Bend Sector of US Homeland Security covers over 165,000 square miles encompassing over 118 counties in Texas and Oklahoma and is responsible for the largest geographical area of any sector in the Southwest with agents being responsible for over 510 miles of river border. Since 2006, additional agents have been assigned to this area and Border Patrol has massively stepped up its recruitment efforts, increasing the number of agents nationwide from 12,000 to 20,000. But while they have always patrolled the southernmost regions of Brewster County – with a population of 9,300 people, it is one of the nine counties that comprise the Trans-Pecos region of West Texas and is the largest county in the State – most were assigned until recently to the northern towns of Alpine and Marathon. But today, they patrol closer to the Rio Grande in remote places like Terlingua – “Before, we had to sit and wait for illegal traffickers to come to us,” a spokesperson had said, “Now we can catch them a little quicker, or get behind them.”

This has lead to some “crabby” local attitudes to the patrols as the roadside stops can be tedious and intrusive in their questioning and searches. We were stopped just 5 miles from Marfa, a good 60 miles up from the crossing at Presidio, but the young guard was pleasant enough and he recognised that my English accent and UK Drive’s Licence guaranteed our probity !

It appears that many residents feel safer here with more agents on the ground, scanning for drug traffickers, but some, who have lived for decades in these isolated areas, see all the added security as overkill in what they believe is a relatively safe region. The only populated border cities of any size for hundreds of miles around are Presidio and Ojinaga, and together those communities number fewer than 30,000 people. The rugged landscape here – jagged mountains and brutal desert line on both sides of the Rio Grande – keeps the drug trafficking significantly lower than in other border areas and, while the Marfa Sector agents have made a number of arrests, these are drastically lower than their counterparts in, for example, Tucson, Arizona, the busiest border sector. So, the Big Bend area’s isolation and forebidding terrain have limited the drug cartels’ ability to infiltrate from the Mexican lands across the river into Brewster County, though some still manage to make it across.

“These counties have been significant drug corridors, but because we’re so huge and spread out, a lot of activity goes unnoticed,” a County Judge said, “We still have traffic, but nothing like the levels of other areas.”

Most of the new Border Patrol agents come from all corners of the United States, some having recently returned from their experiences in the alien worlds of Iraq and Afghanistan, and the residents feel that they are often unfamiliar with the laid-back flow of rural country living. Veteran agents – the ones that people have come to know as neighbours – grew up in the area, mostly in towns like Alpine, Marfa and Fort Davis, and they are active members of their communities. The larger towns are also accustomed to seeing agents tootling around in their white SUVs, touring area schools, eating at local restaurants and coaching little league baseball games. But in far-flung border outposts like Terlingua, the new agents don’t quite fit in.

Some locals feel that the new agents have not made sufficient effort to ingratiate themselves with the community and Border Patrol agents have been known to destroy gates and cattle guards on ranches, although they are legally allowed to patrol private ranch land within 25 miles of the river.

“The government hired so many so fast that they don’t have the etiquette or bedside manner of country life,” one rancher said, “There’s a different way you talk to ranchers and people who live here and make their living in small town communities.”

One agent, a Marfa native who is a supervisor in this sector, said that it takes time and commitment to get used to life out this way and it took him four years to memorize the landmarks and to navigate the threatening desert and mountains, and he still doesn’t know every nook and cranny. But many of the new agents and their families still find the sector’s remoteness and isolation challenging.

You can get to Marfa in a number of different ways but however you do it, it’s a long way from anywhere. You can fly to Midland/Odessa in the north or to El Paso in the west and then get a car to carry you the rest of the way, 200 miles in either case. Or you can get a train to Alpine and then hire a time-car for the sedate 25 mile journey down TX-67. But because we’d chosen to sojourn in San Antonio during Thanksgiving and were now burdened with an extra suitcase stuffed with everything that we’d accumulated during the past 60 odd days of travelling, we took the long road, Interstate-10, to make the 492 mile trek to the town that, once just another Texan cattle town, has become a magnet for hipsters from the metropolises to the East and West or for the simply curious from Texas and its adjoining states who’ve heard that something is happening here, though they’re not sure quite what it is !

By way of illustrating the attraction, I heard about a painting by an artist from New York, who also has property in Marfa, that recently sold for $26 million. “Apocalypse Now,” a 1988 painting by Christopher Wool, was sold at a Christie’s auction house sale of post-war and contemporary art that had taken place in November in New York. But, according to reports, Wool himself would receive nothing from the sale, rather a New York art dealer had bought the work on behalf of a client, the seller being reported as a former member of the Guggenheim Museum’s board of directors who had pulled the work from a current exhibit of Wool’s art at the museum. Wool’s consolation would be that his “art cred” would continue to soar.

Wool was an artist in residence at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa in 2006 and, soon after, he purchased a home and a workspace in the town with his wife, who is also an artist. But, curiously, “Apocalypse Now” features the words – SELL THE HOUSE, SELL THE CAR, SELL THE KIDS – from a famous line in Francis Ford Coppola’s film “Apocalypse Now”, based on the Joseph Conrad novel, “Heart of Darkness.” Which makes you wonder just where Mr Wool’s ideas are coming from !?

But this story begins to elucidate what Marfa has become known for today, namely the Chinati Foundation, or “La Fundación Chinati”, which is the museum of contemporary art established in the town after Minimalist artist, Donald Judd, began to buy up large chunks of property after he had made his first visit in 1971 and had then moved himself and his family from New York to Marfa as a full-time resident in 1977. Construction and installation at the site began in 1979 with initial assistance from the Dia Art Foundation and the Chinati Foundation opened to the public in 1986 as an independent, non-profit, publicly-funded institution.

And it was the Chinati Foundation and its collection of work that was one of the principal reasons why we had decided to make Marfa our last resort in our epic journey !

But first I had my own encounter with Texan Law Enforcement on the way down from San Antonio. The journey was uneventful to begin with, as the traffic was flowing freely on the Interstate and we were making good time. Even though I noticed, at one point, across the carriageway heading in the opposite direction, that a vehicle had been stopped by what looked like an unmarked police car, there were no signs of patrol cars on our side and, on the very smooth, flat and true road our KIA Hybrid hire-car eased its way past the slower traffic.

Until, that is, I obviously went through some form of radar, and I saw, in my rear-view mirror, red and blue lights flashing way back on the far horizon. I thought at first it was police answering some other call but eventually the lawman caught up with me and I pulled over. It was an old guy, a State Trooper, who must have been woken from his dozing by the bleeping radar and who had eventually tracked me down but, after taking my UK licence to check, he just issued me with a warning, which I had to sign for. He said I’d been doing 94mph, which seemed quite generous to me, but I claimed that I’d been observing the 80mph limit. British pragmatism and phlegm won the day yet again !

After that we made two refreshment stops, one in the town of Sonora where we had a cup of coffee in a Dairy Queen that was patronised by some of the largest and most obese specimens of American manhood that we’d so far witnessed and the other in Fort Stockton where we stopped at a Mexican diner, Pepitos Café, for lunch. It was about 14.30 by now, the diner was pretty full, and the waitresses seemed to be particularly harassed in their work as they were being directed by a middle-aged man, who sat at the cash till watching like a hawk monitoring them as they tried to keep up with the demands of the clientele. But the food was alright and not too expensive so it plugged the gap and gave me a little bit of time to reflect on my dealings with the Trooper back up the road.

After leaving Fort Stockton we soon got onto the US67, which I drove down at a noticeably more steady speed, reaching Alpine and then on towards Marfa, where, having settled into The Paisano Hotel, we headed off to the nearby Crowley Theater, just around the corner and down South Austin Street to hear the artist, Roni Horn, give a performance of her monologue “Saying Water”, hosted in coordination with the Marfa Book Company’s exhibition, “Still Water (The River Thames, For Example)” which was on display at the bookstore. Horn’s work “Things that Happen Again (For a Here and a There)”, is also on permanent view at the Chinati Foundation.

The performance was free and the theatre gradually filled up with what appeared to be Marfa’s intelligentsia and visiting hipsters and there was much greeting going on before a figure who had been sitting on a bench in the shadows at the side of the auditorium made their way to a seat at a spot-lit desk in the darkened space at the front of the audience. I must admit that it was only when Ms Horn opened her mouth to speak the opening lines that I realised it was her, as her masculine-looking attire and cropped hair had made it difficult to be sure that this was the female who would be performing tonight !

“In a waiting room in a doctor’s office some years ago, I overheard a mother talking about how her kids were afraid of it. If they couldn’t see into it, they wouldn’t go into it … The opacity of the world dissipates in water. Black water cannot dissipate the opacity of the world. Confused ? Lost ? Large expanses of water are like deserts: no landmarks, no differences. If you don’t know where you are can you know who you are ? Just tumult everywhere endlessly, tumult modulating into another tumult all over and without end. The change is so constant so pervasive so relentless, that identity, place, scale – all measure lessen, weaken, eventually disappear. The more time you spend around this water, the more faint your memories of measure become. Water is a mysterious combination of the mysterious and the material. Imagine something that impinged on by everything, in contact with everything remains to this day mostly transparent – even crystal clear when taken in small enough quantities. Water is transparence derived from the presence of everything. Water is transparence derived from the presence of everything – that is water sifted down, filtered out through the planet Earth – Earth, aquifer that clarifies and realises purity … All things converge in a single identity: water. Water is utopic substance. Among water. Isn’t water a plural from ? How could it ever be singular, even in one river ?”

And so it went on, an intriguing and provocative piece, if long and in places deliberately repetitive, but she delivered it well sometimes pausing for effect, to gather herself, to take a sip of water or occasionally to make the briefest of hesitations. Remembering a conversation with cowboy, Ray, back in a diner in Tatum, New Mexico, about the several-year drought that had been blighting the ranges and ranches, it was a very apt and appropriate subject for this part of the country let alone for the wider world at large.

The following morning we needed to get some washing done and visited the Tumbleweed Laundry, located, again, in Austin Street just before you get to the Crowley Theatre.

The Tumbleweed prides itself as “the finest laundromat in all of West Texas” and the big front loading washers and very large dryers, each machine having his/her own name, is certainly an unusual facility in Marfa. They provide free Wi-Fi and there is a café attached, in an adjoining space, where ice cream and coffee is available for purchase.

In the café I came across a somewhat bizarre installation, “Yo Calvin” which consisted of a number of cryptic notes and messages to “Calvin”, posted across the three walls, and which had been linked together by strands of string. Apparently, the perpetrator just appeared “out of the blue”, as it were, and new messages just got posted up before anyone realised.

The young girl running the laundrette this day said that she didn’t know who was doing the installation, but she had been living in Alabama and had only moved back here recently, so didn’t know too much about the mysterious intruder. She told me that she had moved back to her hometown as she “didn’t like all the trees in Alabama”, whereas here, while there were still some trees, you could see for miles !

Later during our visit to Marfa, on another visit to the launderette, I found that the artist who had been promulgating the “Yo Calvin” story had tidied up the display and put most of the messages in to small envelopes. She also revealed her identity as Megan Belmer, born in 1987, who announced that she had been a student at the Art Institute of Chicago for a “little while” but who was now living here in Marfa.

We finished at the Laundrette and found somewhere to get breakfast at the “Boyz 2 Men” Taco trailer run by a character named David Beebe. The trailer is located in the parking lot of Padres bar/club, and had its seating right outside, in warm autumnal sunshine.

The food was quite good and I had scrambled egg but I didn’t need any of the “chup” offered by the young man taking the orders. When he explained that this was “Ketchup” I commended him on his abbreviation and he made some remark about shortening the language being one of his talents. A little while later two girls came along, one of whom gave a lurid description of her recent ordeal getting treatment in a hospital in Houston and between them they gave us a short lesson in how young Americans were mangling the Queen’s language, if not forging one completely of their own !

Local information has it that “Boyz 2 Men” is located at “trailerland” – a reference, I suppose to the number of ancient Airstreams that are parked on the lot at the corner – serving up daily specials on Saturdays and Sundays and Mr. Beebe has an “online journal of things that are worthy of recording”. On the introduction to the journal, he says that he is interested in “cooking, Airstream trailers, old Chevrolet trucks, Roller Derby, Recycling, The Big Bend region, Marfa, Houston, San Antonio, El Paso, Oldies Rock and Roll, Spanish, Paris, New York, Houston Astros, Rockets & Texans, electrical work, and a lot of other stuff.” He has also started showing films on Saturday nights at his make-shift outdoor theatre.

Later the same day I visited the Lost Horse Saloon on East San Antonio Street and learnt that David Beebe and his band had played in the bar the night before where there was still some of their amplification and a pedal steel guitar on the low stage. I was told that some of the equipment had already been taken away by members of the band, as they were playing in Terlingua that evening, but they would still have to collect the rest of it. The young woman working behind the bar said that it had been a raucous evening with a mixed crowd, including locals and cowboys, and that there had been plenty of Texas two-step danced. The band had played pretty much non-stop from 20.00 until 11.00 and, in spite of his exertions, David Beebe must have got up early this morning to do the cooking at “Boyz 2 Men”.

I took a few pictures over the road opposite the trailer and when I came back was on my way to have a look at Padres – one of Marfa’s best live music venues – where I intended to attend a gig in the evening when another customer of “Boyz 2 Men”, standing near the trailer having a cup of coffee, spoke to me about Padres being closed and, with this opening, we got into a conversation. He turned out to be an interesting character by the name of Glen, with an interesting backstory.

Glen’s journey in the contemporary art world has been a long and varied one, starting at Dayton’s “Gallery 12” in Minneapolis when department stores were different to how they are today. Dayton’s was one of the mid-west’s most successful department stores and in the mid-1960’s they were also one of the foremost galleries of the contemporary art world, introducing America to Joseph Beuys and showcasing works by Warhol, Rauschenberg, and Lichtenstein just a few floors above homewear and the shoe department. And Glen bought one of Warhol’s “Marilyn” prints for $120 dollars on his Dayton’s charge card !

When the Dayton Gallery 12 closed in 1974, Glen began dealing art from his own home, building the beginnings of a vast network of artists, collectors and musicians that continues to grow to this day. At first there was no money in art, it was just smart people who were friends that helped each other and one such friend would end up running his own gallery, showing work by Glen and other artists. Around this time, Glen also helped some local bands, playing guitar for transplanted blues musician, Lazy Bill Lucas.

By 1976 Glen had become a partner with a fellow collector and had opened his own Gallery in the warehouse district of Minneapolis, the first gallery in that part of town and one which he ran like Dayton’s – because that was all he knew. Other galleries would take 20 or 30 different pieces on consignment while he was taking ads out in Artform, buying wine for the openings, and inadvertently raising the bar for the art scene in Minneapolis. Being at the centre of a burgeoning artistic scene was an incredible thing and Glen recalls this special era as an infectious one.

Like all good things, the gallery didn’t last long and, by 1981, he was working as a corporate art consultant, travelling the world and acquiring pieces for some of America’s largest corporations as it was a trend for the major companies to have a collection of artworks, another merit badge for them. He was flying all over the world – to art-market places such as Milan and Düsseldorf – and living in apartments in Manhattan that no one else used. And while the commodification and commerce of art was increasing, Glen was still trying to push the envelope in terms of content.

A few years later, Glen left the corporate consulting world and, as he found himself at a crossroads not having had to make a real decision for almost 20 years – having just ridden the wave – he now had a decision to make as to whether to go either to New York or to Los Angeles to continue to climb the ladder. But he chose Minnesota instead, going back home, buying a house out in the country and getting a real estate license. But it didn’t go exactly as he had planned as he tried to sell rural real estate during the farm crises and he soon found himself with a collection of odd jobs – delivering mushrooms from the farms to the cities, teaching art classes at local colleges, and starting a country-western band. It was during this time that Glen was also first introduced to the beading process that would become the main focus of his artistic practice for the next two decades when a friend of a friend, who mostly lived in a teepee in the Black Hills, came to crash at his house and he made Glen a guitar strap from elk hide and taught him an old Lakota style of beading called ‘lazy stitch’, a common form of Sioux beading that, while simple, is extremely time consuming. Some of Glen’s larger pieces contain 11,000 beads, all individually selected and threaded to make a continual, flowing pattern, but Glen says that anyone could do this if they had the patience, though very few people do. The discipline of the bead work spoke to a place in Glen’s life that enjoyed simplicity and peace and, in 1991, shortly after beginning to bead, he joined a Benedictine monastery and was a monk for six years. When pressed as to whether he had an overarching motivation or spiritual calling, Glen recalls that, as Wittgenstien said, ‘if you ask why, you’re looking for a cause or justification.’ He had neither, he just did it.

During his time in the monastery, Glen continued his bead work and his first exhibition, “Following A Rule”, took place in 1994 and included several lazy stitch pieces. He described the show as “… art about the difference between explanation and understanding” but, just as suddenly and inexplicably as Glen had entered monastic life, he departed from it. When asked if he felt whether he had achieved any sort of spiritual epiphany that led to his departure he replies, “No. No. No. No. No. I just left. I was just ready to go.”

Returning to Minneapolis, now very much changed from the artistic scene of the late 60’s, Glen was welcomed back as an artist and musician. “It’s weird ’cause I don’t claim to be an artist or a guitar player or anything. It’s just different stuff I do.” These different things that he did still had a vital place in the close-knit community of the Minneapolis art scene, including a new country band that consisted of singers Page Burkam and Jack Torrey, of “The Cactus Blossoms”.

Soon Glen sought to escape the harsh Minnesota winters by traveling through the southwest in his restored Toyota Chinook, a customized camper that he also uses as his studio, and he eventually made his way to West Texas and set up shop in Marfa. The show “Blinky, We Hardly Knew Ya” was his first in the town and came quite unexpectedly. “I never look for shows. They just kind of happen. It’s a real treat and the whole thing is stuff I’ve made since I’ve been here.” The show was a nod to German abstract painter, Peter Schwarze, who adopted the moniker of a famous American mafia capo, Blinky Palermo, and painted the 1976 series “To the People of New York City”, which influenced Glen a great deal.

Glen’s bead work is rich and precise and the colours shimmer off the hides with the level of skill necessary to make them immediately evident. “It’s like blues or country music. You’ve got 12 bars. I really just enjoy restricted forms.” Glen’s work still reflects his organic spiritual inclinations and, while no longer in the monastery, he still attends church regularly and looks at his beading as another form of prayer. “It’s calming. When things get fucked up I just keep beading and it comes together.” While he has created detailed landscapes and intricate pattern work in the past, his pieces offer a simple and earth tone palette. One set of pieces is entitled “The Four Seasons”, a group of four small works with shifting, complementary colours. “I made Winter and Summer first before I knew what was happening” he explained, “Then I said ‘Aw fuck!’ and I’ve been beading for three days straight. I finished at 9.30 this morning and came and hung them up.”

Glen’s contributions to the contemporary art world have been eclectic and enduring, his greatest being that he is simply still involved and in such a vital way. In a town like Marfa, Texas, where the two aspects of the art world – grassroots local artists & international jetsetters – are in such close proximity, Glen is a modest man who has seen enough changes in each to exist in both.

We spoke about Rauschenberg with whom he had worked on a couple of exhibitions in Minneapolis and about taking up the guitar again after a hiatus because of our lack of conviction in our own ability, but that now we were both ready and thinking about starting again. He recommended Billy Joe Shavers and The Cactus Blossoms as musicians to listen to.

I told Glen that I would be visiting the Judd works the following day, Sunday, and he mentioned a “Valerie” whom he said was an excellent guide and would probably be doing the tour tomorrow. I took a couple of pictures of him and got his email contact.

After this long conversation, we returned to The Paisano from where I took off to reconnoître what Marfa had to offer by way of Art, other than that made and collected by Donald Judd.

I started at the Ayn Gallery where I saw some of the worst paintings that I’d come across in a long while. These were 18 works by a German artist, Maria Zerres, her monumental elegy, “September Eleven”, completed between November 2001 and February 2002 in the wake of the tragic events of 11 September 2001 in New York City where the artist has lived and worked for many years. Zerres has said that she was deeply affected by the violent destruction of New York’s twin towers and has described the towers’ office light as a sort of beacon for her life as she walked with her children at night in the area around her apartment. But, even allowing for the horror of what she was depicting, which I assume she felt she could only approach through a kind of dumn simplicity, the paintings were awful !

Then in the room next door there was a selection from Andy Warhol’s largest and most comprehensive series, “The Last Supper”. Commissioned in 1984 by gallerist, Alexandre Iolas, Warhol created more than 100 paintings and works on paper based on Leonardo da Vinci’s painting which is housed in the the refectory of the Convent of the Santa Maria della Grazie in Milan. The works on show here were characteristic of Andy’s tongue-in-cheek pop culture references, that is, they were simplistic, line-drawn cartoon images – another disappointing, over-blown exhibition.

After this, I decided to go for a beer, which I found in the Lost Horse Saloon. I was the only customer, other than a cowboy sitting at the bar, and I wandered around with my Shiner beer looking at the cow skulls and the obligatory Texas Longhorns’ horns mounted above the bar. They also had two pairs of decorated cowboys chaps hanging on a wall next to the pool table and a beaten-up old upright piano, a relic perhaps of some earlier time. The barmaid said that she had just relocated to Marfa from the east, that is from New York, and really liked the lifestyle that she’d found down here.

There was due to be a poker tournament taking place in the saloon later but I wasn’t going to wait for that to start and I left and walked up East San Antonio Street towards the traffic lights and went into “fieldwork/marfa”, an International Research Program, run jointly by Les Beaux-Arts de Nantes and HEAD-Genève. The programme has residences for artists and I spoke with the young man who was looking after the gallery and sweeping up seemingly in preparation for the installation of a new exhibition. He said that he had himself studied in Nantes and I told him about an English artist friend of mine who had also spent time there undertaking post-graduate study.

There was some photographic work and documentation by someone named Elisa Larvego which caught my attention which was based on the artist’s investigations of a specific community on the Mexico-United States border and this warranted further investigation.

In 2011, Elisa Larvego, who is based in Geneva, was invited to take up the artist-in-residence position for three months at “fieldwork/marfa” and she soon became interested in a nearby village on the US side of the border by the name of Candelaria, with about one hundred inhabitants, including almost sixty children, located where the road stops in the Chihuahuan Desert. It is situated across the Rio Grande from San Antonio del Bravo in Mexico, but there is no direct transport link between the two villages.

In the 1990’s, the American government closed down the school in Candelaria, officially for financial reasons while, on the Mexican side, there is no school or school bus, as the dirt road linking the village to the only town in the area, Ojinaga, is very bad.

The only possibility for the children to receive an education in Mexico would be for them to move to a town in the region, but most of the families have land in San Antonio del Bravo and don’t want to leave their village. So, the children have to travel three and a half hours every day by bus to attend the school in Presidio, the frontier town that we’d visited down on the border, in the US. Most of the menfolk live in San Antonio del Bravo and, at weekends, the residents leave Candelaria to join their families on the Mexican side.

In the 1990’s, the inhabitants clubbed together to construct a footbridge, creating a permanent link between the two villages but passing from one country to the other was still illegal, although it was tolerated by the US government until 2008, when the bridge was destroyed by the authorities. Inhabitants wishing to cross the frontier legally then had a five-hour drive to reach a village only a matter of feet and yards away as the crow flies.

In 1920, in order to reduce erosion in the Rio Grande valley, which posed problems for the US government, the American authorities introduced the salt cedar, a kind of tamarisk, a species of tree from North Africa. Given that the river delineates the boundary, the constantly-shifting river bed of the Rio Grande also meant that the frontier kept changing so the salt cedars were intended to stabilize the river bed and so establish a clearly-defined boundary. After their introduction, the authorities noticed that the trees were enormous water consumers and a highly invasive variety as this tree species secretes salt into the ground, hence its name. It was discovered that this characteristic inhibits all other sorts of trees or plants from growing in proximity to a salt cedar and the region gradually dried out and the salt cedar soon became the only variety of tree left in the valley.

In 2010, the American government tried to eradicate the salt cedars by introducing a species of beetle from Tunisia and the trees do appear to have died since the arrival of the insects, but the latter have also wiped out another sort of tamarisk, a tall, evergreen variety, not invasive or destructive like the salt cedar, which was planted to provide shade near houses and ranches. These trees were much appreciated in this desert region and their disappearance is problematic for the valley’s inhabitants. The other negative consequence of the introduction of the beetles is the creation of a forest of dead trees that often catches fire in the spring, sometimes five times a month.

The cause of these fires is still a mystery but, according to the region’s American inhabitants, they are accidentally started by local farmers on the Mexican side, where there are no regulations. However, some Candelaria residents think that the fires might be deliberately lit by American border patrols to prevent Mexicans from hiding in this dead forest. It is rare that the firefighters come to extinguish these frequent fires as Candelaria is too isolated and so the valley has become known as “the forgotten valley”.

So, a bridge there had recently been destroyed and this was mentioned to Elisa by one of the inhabitants and it aroused her curiosity. She went to Candelaria and was surprised to find just a small hamlet, a kind of ghost village, where there was no café and no shop and where she sensed that it would be difficult to meet the people living there. But, as she was leaving, she happened to pass the school bus coming back from Presidio and she realised that the children made this long journey every day. Later, she learnt from press cuttings that the school in Candelaria had been closed down without justification in 1998 by the US government and she came to understand that the families were divided between the village of San Antonio del Bravo in Mexico and Candelaria in the US, so that the children could receive an education and she was very interested in this separation of a family unit by a boundary, for it gave her the chance to observe closely how territory can determine identity.

The division also leads to territorialisation by gender – the men stay in Mexico to farm their land and tend to their animals, while the women spend the week in the United States to enable the children to go to school. This relationship between the inhabitants and their context – geographical, political and environmental – has interested Elisa for many years and she has already studied this connection in several of her previous projects.

Now this frontier between the “first” and the “third” world is a very real and highly militarised border, crystallizing the absurd inequality between human beings and, over and above the political geography, Elisa’s work deals with the spatial practices that develop there, in the form of tactics and games, in everyday life.

The Mexico-United States border has featured in many photographic or film documentaries, yet the Candelaria region doesn’t tally with the generally accepted idea of this highly-guarded frontier with its walls stretching for miles. It is not a migration transit point but a kind of vacuum, an area abandoned by the authorities. Crossing the frontier doesn’t lead to the other, the unknown or the stranger, but to a familiar place, another home. It was the uniqueness of this context that made Elisa want to start work on this region.

After her first encounter with Candelaria, she felt that this project should focus on a child’s viewpoint and she didn’t want to carry out interviews, but rather let the images speak for themselves by following a child around in their daily life, between their journeys to and from school, their life in Candelaria and their return trips to San Antonio.

In due course, she came into contact with Pilar Avila who lived in Candelaria until the school was closed down and who had subsequently gone to live in Marfa so that her children didn’t have to make the journey by bus every day. She had a house in Candelaria where she suggested Elisa could stay and, while there, she invited her to meet her family and so Elisa met Clarisa, a seven-year old girl who quickly captivated her by her open temperament and she decided to focus her project on her. The girl quickly introduced her to her circle of friends and neighbours and she was therefore able to follow her around as she played, either in the riverbed or in the village of Candelaria. Elisa soon found the childrens’ games fascinating, as they added a new dimension to the place. By transforming the border into a playground and by introducing a touch of lightness through their constant laughter, the children highlighted, through playing tag or fearing the arrival of the police, the dangers inherent in this river channel, where any presence is forbidden. These moments brought two different worlds together and made them interact, the almost dreamlike one of play and the very real world of border illegality.

Clarisa’s family, composed solely of women on the American side of the boundary, generously introduced Elisa to the life of the village and the private world of their family unit and meeting this family gave her a gradual understanding of these inhabitants’ unique situation, living divided between two countries. In fact, she was able to forge ties of confidence with them by spending time living there and by building up a relationship with each of the women.

Clarisa lives with her great aunt, Antonia, and she shares a bedroom with her mother, Adriana, her aunt, Lupita, and sometimes her grandmother, Clara, and Elisa’s attachment to these three generations of women grew out of the evenings that she shared with them. It was also this attachment that primarily led her to carry out this project, inspiring her to relate their singular living conditions in both still and moving images.

Elisa mainly worked with the moving image when dealing with people, whereas her interest in the location was expressed through photography. The only photographs she took of the families were at their request but this separation between media usage came about naturally as she wanted to follow Clarisa in movement and not freeze her in a certain time and place and video gradually allowed her to enter the life of the young girl, at the same time evoking her environment.

The photographic work developed little by little, through hearing the story of the introduction of the tamarisk trees and, after having witnessed some of the fires, Elisa asked around about their possible origin. The replies, like the history of these trees, seemed to crystallise the conflict situation in this region. This also established another type of connection between the environment and its inhabitants – not just people being determined by their context, but also a transformation of place as a result of human beings and their conflicts.

The photographs enabled her to record the state of the lands ravaged by fire after the event but they also allowed her to document the traces of the conflict in this environment, such as the remains of the footbridge or the cables suspended above the Rio Grande. However, she also filmed these spaces to show the violence of the fires and their ongoing progression, as well as to situate Clarisa in the context of this vast desert landscape.

Elisa visited Candelaria at two different times of the year which enabled her to see the village in two different lights as there are only two seasons in the region – winter and spring – and everything – the vegetation, the light and the pace of life of the inhabitants – changes from one to the other.

In Winter, the landscape appears almost black and white with short evenings, while Spring brings colours and a brightness which lasts until late into the night.

She first discovered Candelaria in the winter, then returned there in the spring, which meant that she could observe how Clarisa’s life changes with the seasons – in Winter, she goes back home early, around six o’clock, when the sun goes down, and rejoins Adriana, Lupita, Clara and Antonia around the stove while, in Spring, she stays out until half past nine, playing with other village children near the only streetlight. In Winter, the atmosphere in the house is more taciturn but, in Spring, sounds and words fill the spaces and the women in Clarisa’s family confide freely. If Elisa hadn’t visited on two occasions, she would never have discovered these two aspects of the same place and of a single life, which has allowed her to reinforce the connection between Clarisa’s environment and her daily life.

Elisa feels that, through this project, she has discovered that it is possible to live divided between two countries – in this case, the United States and Mexico – by illegally crossing the border every week and she was astounded by this, as she’d never imagined that such a “non-zone” could exist on this now mythical frontier. She was also struck by the fact that this separation of the families is due to the parents’ desire to give their children an education and, indeed, these mothers sacrifice a significant amount of their conjugal and social life during the time their children are at school, in the hope of giving them a better future. The work has strengthened Elisa’s conviction of the importance of the link between a place and its inhabitants for it was the first time she’d been able to observe such a relationship to a territory in the people living there and the way in which this relationship shapes their lives according to the geographical reality of these fragmented areas. It was also the first time that she’d observed the repercussions of a political and social situation on an environment.

The issues associated with borders, along with environmental concerns, seem to lie at the centre of our problems in the world at large today and it is not surprising that young artists, such as Elisa, feel compelled to address such subjects in their artistic expression. It was such a refreshing discovery to come across her work which only served to show up even more the simplemindedness of what I’d seen earlier in the Ayn Gallery.

In the Marfa Ballroom, another gallery, as part of an exhibition entitled “Comic Future”, I saw work by the artists, Mike Kelley and Paul McCarthy.

“Comic Future” featured work by several artists who “employ the language of various and discordant approaches such as abstraction and figuration to twist representation of their immediate environment thereby imbricating a skewed, often apocalyptic vision of the future”. Showcasing works from the 1960s through to 2013, the exhibition surveyed political satire and cultural commentary through art movements ranging from capitalist realism to contemporary pop art. The works included early drawings by Sigmar Polke, collage by Walead Beshty, painting by Carroll Dunham and Peter Saul, alongside newer works by Dana Schutz, Sue Williams, Michael Williams and Erik Parker and sculpture by Aaron Curry, Liz Craft and Mike Kelley. A Ballroom-commissioned site-specific wall installation by Arturo Herrera completed the show.

Drawing from the art-historical lineage of cubism, cartoons, figurative painting and gestural abstraction, and appropriating subjects from mythology, advertising, print culture and consumerism, “Comic Future” was as much about the breakdown of the human condition as about the absurdities which define the perils of human evolution.

I was particularly interested in seeing the work of Mike Kelley’s, an American artist, whose death in 2012, in an apparent suicide in South Pasadena, California, rather shocked people in the art world.

Kelley’s work involved found objects, textile banners, drawings, assemblage, collage, performance and video and he often worked collaboratively and had produced projects with artists Paul McCarthy, Tony Oursler and John Miller.

Kelley is widely regarded as one of the most influential and prolific post-Pop contemporary artists whose work mined American popular culture and incorporated cultural references and everyday objects like plush toys, exploring themes of class relations, contemporary sexuality, repressed memory, systems of religion and politics, and, ultimately, transcendence. He has been described as “one of the most influential American artists of the past quarter century and a pungent commentator on American class, popular culture and youthful rebellion.”

Shortly after news of his death broke, a spontaneous memorial was built to him in an abandoned carport near his studio in the Highland Park section of Los Angeles where mourners were invited, via an anonymous Facebook page, to “help rebuild MORE LOVE HOURS THAN CAN EVER BE REPAID AND THE WAGES OF SIN (1987), by contributing stuffed fabric toys, afghans, dried corn, wax candles … building an altar of unabashed sentimentality.” The memorial was active throughout February 2012 and was dismantled in early March 2012, with the contents given to the Mike Kelley Foundation.

Kelley’s works in the Marfa Ballroon show were sculptures from his “Kandor” series made in the period 1999-2011. “Kandor” refers to the capital of Krypton, the home planet of DC Comics hero Superman, who believed he was the sole survivor of his doomed planet until he discovered that Kandor had been miniaturized by an archenemy. Colourful and delicate, yet eerily oozing sculptures made from luscious looking and brightly-hued hand-made glass, these works depicted the fantasy city.

McCarthy’s work, “Painter” of 1995, was a humorous and ironic, spoof movie documentary of a “painter,” pacing and unsettled, who enters a room muttering to himself as if he were crazy. The opening scene of the 50-minute video saw McCarthy playing the main character who wears a giant nose, a blonde wig, and a hospital gown. He has massive hands and elephantine ears but only a few objects fill the set – oversized, Oldenburg-esque tubes of paint, a table, and a floor-to-ceiling blank canvas. Occasionally, as if in an attempt to address the audience, McCarthy voiced animalistic grunts between intelligible statements such as, “Try to listen, try not to think, try to see things my way.”

McCarthy’s caricature of an artist resembled devices variously used to attract the attention of children and he seemed to be setting up the content of an instructional video on how to paint, but was unable to perform this task as the character digressed into schizophrenic breakdowns. After placing his hands on his head in dismay, the character spun in circles, endlessly repeating “De Kooning, De Kooning, De Kooning”. He tried to paint, but ultimately created nothing more than a mess of materials, covering the room and the canvas. Finally, the painter muttered to himself, “Don’t try, you can’t do it anymore, Don’t think about those people out there.”

McCarthy’s work often seeks to undermine the idea of “the myth of artistic greatness” and attacks the perception of the heroic male artist – enuff said !

Marfa Ballroom has also been involved in contributing to the financing of the creation of another satirical artwork in the area, this one being “Prada Marfa”, a permanently installed sculpture by artists Elmgreen and Dragset, which is situated 1.4 miles from Valentine, just off U.S. Route 90, about 37 miles northwest of Marfa. The installation was inaugurated in October 2005, the artists calling the work a “pop architectural land art project.” The sculpture cost $80,000 and was intended to never be repaired, so that it might slowly degrade back into the natural landscape but this plan was deviated from when, three days after the sculpture was completed, vandals graffitied the exterior and broke into the building stealing handbags and shoes.

Designed to resemble a Prada store, the building is made of adobe bricks, plaster, paint, glass pane, aluminum frame, MDF, and carpet. The installation’s door is nonfunctional and, on the front of the structure, there are two large windows displaying actual Prada wares, shoes and handbags, picked out and provided by Miuccia Prada herself from her fall/winter 2005 collection – Prada allowed Elmgreen and Dragset to use the Prada trademark for the work having already collaborated with Elmgreen and Dragset in 2001 when the artists attached signage to the Tanya Bonakdar Gallery in New York City with the “false” message “Opening soon – PRADA”.

As “Prada Marfa” is located relatively close to the Chinati Foundation, the minimalism of Prada’s usual displays are mimicked in this work and play off the kind of work that Donald Judd was known for as an artist.

The Texas Department of Transportation is currently discussing the fate of the installation now that it considers it a billboard that does not fit permitted specifications, but no finalization has been made regarding the installation and its location.

The next gallery along East San Antonio Street that I came to was “Marfa Contemporary”, opened in 2012, the first regional extension of the Oklahoma Contemporary Arts Center, a nonprofit organization which is dedicated to encouraging creative expression in all its forms through education and exhibitions. Shows at Marfa Contemporary are free to the public year-round and feature recent works by regional, national and international artists and classes and workshops for children and adults are also offered throughout the year at minimal cost.

The gallery shares a location with the “Pizza Foundation”, adding yet another layer to the multi-faceted, innovative space – pizza being the American cultural equalizer for the class system and, thus, helping the gallery to place middle-America at the fore in an art world that has always been dominated by the East and West coasts. The interior space, designed by Oklahoma City-based architect Rand Elliott, adheres to the architectural makeup of Marfa, showcasing cracks and bare brick in a way that adds texture and substance to what otherwise might have emerged as a sterile setting,

The work on show at the back of the Pizza area had some delicate, machine-cut, embroidery-like work in an exhibition titled “Walking, Eating, Sleeping” by an artist named Laurie Flick whose ideas explore the intersection of technology and creativity. Apparently, the artist herself adopts a daily regimen of self-tracking that measures her activities and body and, in so doing, she has shaped a vocabulary of pattern used to construct her intricately hand-built works and installations. Her quantifiable patterns – like her heart rate, the duration of her sleep or her body weight – are some of the metrics that inspire her colourful and complex works.

I crossed Highland Ave and went into the Marfa and Presidio County Museum, housed in the Humphris House, an 1880s adobe home, which had displays about the history of Marfa and the surrounding area.

There was a well-dressed lady sitting in the entrance hall and, when I commented on how warm she had got it inside, she proceeded to tell me about the Ice Storm that had occurred the weekend before which had caused widespread power outages across the Big Bend area and the South West, an unusual occurrence not seen here for a long time.

In the Museum rooms I started by looking at the Paleoindian Period – ca. 9500 to 6500 BC. Little is known about the groups of peoples that entered the Big Bend area at this time but current theories are based on archaeological research in the Great Plains and Lower Pecos region which indicate that the groups were small in number and nomadic and that they were hunters and gatherers who sought after and followed giant bison, mammoths, mastodons and camels as well as smaller animals such as deer and turtles. They gathered seasonal plants for food and medicinal purposes and their main hunting tools were the hand-held spear and an “ataltl” or dart-thrower, a device which greatly increased the distance and throwing force of the dart and which allowed the hunter to stay a safe distance away from large, dangerous game. The groups lived primarily in open campsites using temporary, makeshift shelters and they made stone, bone and wooden implements such as spear and dart points, stone choppers and scrapers, travelling great distances to find specific kinds of raw stone for making tools

Then I moved onto the Archaic Period – 6500 BC to 700 AD – a time of hunters and gatherers with an increasing reliance on plants for food. These were nomadic peoples, who became more territorial due to changes in climate and the availability of needed resources. Climatic changes from a wetter to a drier environment made food and water resources more scarce and forced more diversity in diet and there was hunting of bison, deer, rabbit, turkey and many other animals, the main hunting tools continuing to include the handheld spear and “ataltl” along with a boomerang shaped stick – a rabbit stick – that was used to hunt small animals. New tools were made and used to process plant foods and these tools included the “mano” and “metate”, mortar and pestle – both used to grind seeds, nuts and roots into a kind of flour – stone knives, scrapers and choppers. Fibres were extracted from sotol, lechuquilla and yucca and were used to make sandles, mats, baskets, netting and cordage. The peoples lived in temporary, makeshift shelters in open campsites as well as in rock shelters and caves and rock art began to appear in the form of pictographs – painted images – and petroglyphs – carvings – on cave walls and large boulders.

After this came the Late Prehistoric Period – ca. 700 to 1535 AD – in which the bow and arrow were introduced and eventually replaced the “ataltl”. People hunted bison, deer, rabbit, turkey and other small game and engaged in fishing as well to produce an additional source of food. In the Big Bend area, along the Rio Grande and Rio Conchos, the “La Junta” cultures became semi-sedentary agriculturalists and villages composed of pit houses were built.

The “La Junta” cultures began using river floodwaters for temporary farming and grew crops such as corn and beans with ceramics becoming commonplace in these semi-sedentary cultures since domestic crops could be stored. Trade continued to be important in the lives of the West Texas peoples and probably involved some agricultural products grown by the semi-sedentary groups. Trade networks established in the Late Archaic period increased and included traded items such as seashells from the West Coast.

Finally, I reached the Early Historic Period – ca. 1535 to 1800 AD – when the arrival of European explorers, initially the Spanish “entradas”, radically altered the lives of the Native Americans in the Big Bend.

“Presidios”, or forts, and missions were established in the area, the “presidios” being garrisoned fortresses where soldiers attempted to maintain order among the neighbouring Native Americans and which provided protection for colonialists and missionaries. The missions were built near to the “presidios” and had the religious conversion and assimilation of the Native Americans as their goal.

During this period, several waves of intruding Native Americans from the Plains – initially the Apaches and Comanches – wreaked havoc on the native inhabitants of the Big Bend area as the introduction of the horse by Europeans allowed greater mobility for the Native Americans. The horse enabled rapid southward movement of Apache groups into the Trans-Pecos area thus facilitating raids on local Native Americans and settlers. Iron, also introduced to North America by the Europeans was highly sought after by Native Americans who used it to produce iron arrow points, which rapidly replaced points of stone.

There were some arrow heads from the Clovis people (9200 BC), the Toyah (1400-Historic) and the Plainview (8150 BC) on display.

The museum moved on to show the development by the Europeans after 1800 with many objects and artefacts from the ranching and cowboy community until I reached some interesting documentary photographs of life in Presidio County by Francis (Frank) Duncan.

Duncan was born in Missouri in 1878 but, as a child, he and his parents lived in California and Texas where his father attempted to grow wheat. His efforts, however, were stymied by ranchers who said the land was made only for grazing livestock.

After the death of his parents, Duncan returned to Missouri to live with his grandparents on their farm but he was involved in a train collision in which he suffered a head injury and was declared dead by three doctors. But while the undertaker was preparing him for burial, Duncan woke up and later fully recovered !

He trained as a photographer, returned to Texas to work and then decided to “go up into Canada fishing.” An avid outdoorsman and hunter, he arrived in Salmon Arm, near to Kamloops in British Columbia, in 1913, and opened a photography studio above a store. He was a widower at the time and sent for his daughter, Kathleen, whom a family, the Reilly’s, took care of while Duncan tried to make a living.

To supplement his studio work, Duncan sold subscriptions to the local newspaper, the “Observer”, and he bartered exchanges for his catches of fish. The “Salmon Arm Observer” notes that Duncan was an experienced photographer when he arrived in the area who had specialized in railroad and newspaper photography and who had worked throughout Canada, the United States and Mexico. The “Observer” commissioned him to take photographs of all parts of the Shuswap, a local lake and, in June 1914, the editors noted that Mr. Duncan had a hydroplane that he used on Shuswap Lake.

Duncan later worked in Klamath Falls, Oregon, before moving again to Texas where he made homes in Presidio, Terlingua and, finally, in Marfa, in 1916. According to “The Big Bend Sentinel”, Duncan considered himself a mining prospector first and a photographer second.

He tried to get a piece of the action when mining was big in Terlingua and Shafter, asking to prospect, but was denied access by the local ranchers who discouraged prospecting. Then, as a back up, he offered to take portraits of the ranchers’ families and of the landscapes on their ranches. As one of the earliest photographers in the Big Bend area, Duncan’s motto was – ‘I make faces for a living’ and his black and white portfolio rivals that of the area’s other pioneer photographer, the late W.D. Smithers of Alpine. Both photographers chronicled the US army presence in the Big Bend area in the early 20th Century and they photographed events and places on the border, landscapes in Far West Texas and the local communities while making portraits of the area’s pioneers and residents. Duncan photographed the life and times of Marfa and Camp Marfa, later Fort D.A. Russell, but also wandered with his camera throughout Far West Texas, documenting the ranching and mining industries.

Duncan perfected the use of the panoramic camera, which took extra-wide angle photos and prints from these photographs were between three feet and four feet wide but, at the same time, quite narrow. Many photographs of Camp Marfa and Fort D.A. Russell are in this format. The Marfa Presidio County Museum houses 2,200 of Duncan’s glass and film negatives from the region.

Duncan loved hunting, fishing and the outdoors and he died in July 1970 at Big Bend at the age of 91. During his lifetime, he sold and gave away many prints and negatives and his collection was donated to the Marfa Public Library and later to the Marfa and Presidio County Museum, after acquisition from a party other than Duncan himself by the Marfa High School’s Junior Historians club, having been found in the basement of a Marfa house where it was deteriorating.

In the hallway of the museum I came upon a cache of photos of the making of the movie for which Marfa is most well-known – before Don Judd’s arrival – its only other claim to fame – “Giant” directed by George Stevens of 1955. Stevens shot “Giant” substantially around Marfa, notably at Reata, with its stars – James Dean, of course, Elizabeth Taylor and Rock Hudson but also the very young Dennis Hopper, Sal Mineo and Carroll Baker.

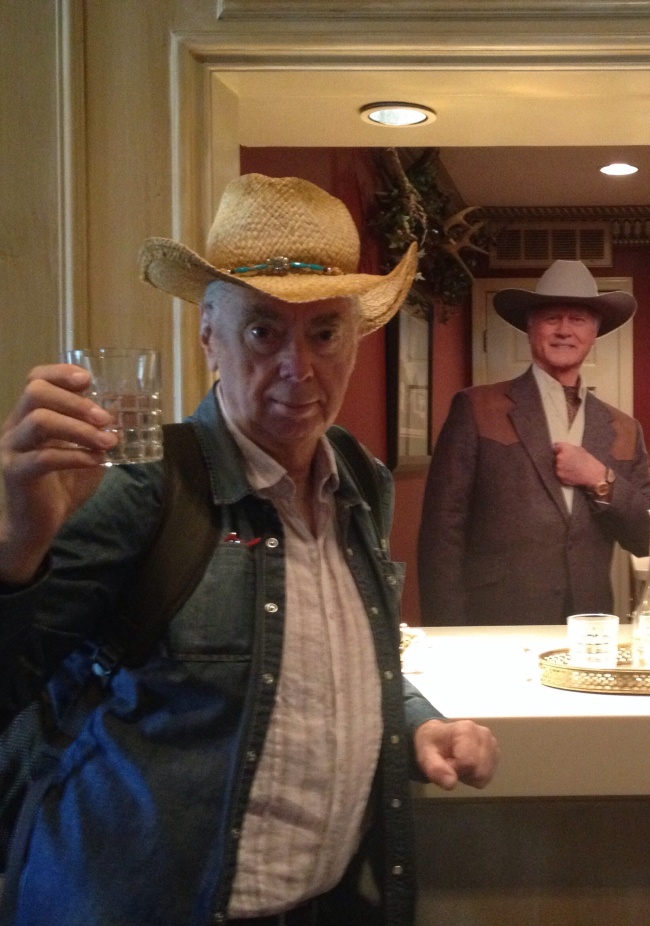

Dean, Taylor and Hudson stayed at The Paisano hotel, where we ourselves were also staying, with their rooms located on the first (second, in US terminology) floor and the hotel makes a big play of the fact with a small room, just off the entrance hall, dedicated to the film with souvenirs, DVDs and photos for sale.

I got talking to the lady attendant in the Museum, a locally-born woman named Bertha, who, as a child, remembered seeing Elizabeth Taylor perform a faint 27 times on the film set one day when a steer’s forehead is cut open and the brains pour out onto her plate for dinner – that, to her, was professional acting showing great fortitude, as Liz continued to try to get the best take ! But she said that Liz was not very approachable, unlikely Jimmy Dean, who was a charmer, always smiling.

We talked a bit about Don Judd’s coming to Marfa and whether there had been resentment by the locals at his buying up so much property and she said some felt like that while others accepted that the farms were closing and that the old ways and businesses had had their day.

I thanked her and moved on to the Marfa Bookstore where they had an exhibition of Roni Horn’s large annotated water photographs, an interesting corollary to her reading that we’d attended on our first evening. In the bookshop, I made a note of several book titles on the drug wars being fought around Juarez and bought two CDs, one by Terry Allen and another by “The Cactus Blossoms”, recommended earlier in the day by Glen, the beadist.

Marfa doesn’t look like any of the surrounding towns in Far West Texas and outsiders come to soak up the diverse culture of this former ranching town, now that it has become an art oasis in the desert, a town more cosmopolitan than any older resident could have imagined. For example, the nationally distributed “Smithsonian Magazine” listed Marfa as No. 8 among “The Top 20 Best Small Towns in America” in a recent issue.

“It’s just a flyspeck in the flat, hot, dusty cattle country of southwest Texas – closer to Chihuahua than Manhattan but Marfa is cooking”, the magazine suggested, “thanks to an influx of creative types from way downtown – filmmakers, indie rock bands and others who have brought such outré installations as Prada Marfa, a faux couture shop in the middle of nowhere.”

They say that the mentality of the community has shifted and that the town nowadays has become more progressive and willing to look at new possibilities. But there is definitely a gap between the old Marfa and the new Marfa and a good many people in the established community feel like the town has been overrun with a different kind of people, people with worldly ideas, people with open minds to different kinds of lifestyles and that has caused a kind of friction.

Some resentment has to do with money, the disparity between newcomers and older families with modest means and deep roots in Marfa with the “creative people” being a bit louder and more flamboyant than the locals. But, it has been said that, without them, the whole community would have folded and collapsed and, generally, Marfa must be better off with the new direction that it has taken.

And the person responsible for this transformation is the now-deceased New York sculptor and critic Donald Judd who started Marfa’s journey into the future as an arts colony in the 1970s when he bought and restored various properties in Marfa.

Judd’s work still attracts visitors from across the world to the two Foundations, the Donald Judd and the Chinati, with the latter running a museum and sculpture park on that used to be the Army camp on the southern outskirts of Marfa and I made my way, in due course, to the Chinati, located on Cavalry Road, not far out to the south of town.

It was a Sunday morning and I was due to go on the 10.30 tour but, while I was waiting, the tour group leaving at 10.00 was getting ready to start, so I asked if I could join them. This was a fortuitous decision because the tour guide was Valerie Arber, a local artist and the wife of the printmaker, Robert Arber, who has a print studio in town. Valerie’s name had cropped up in my conversation with Glen the day before and she proved to be very knowledge about Judd whom, she said, she had met socially about four times while he was still alive after she and Robert had moved to Marfa in 1998.

The museum’s collection is housed in fifteen buildings spread over a campus of 340 acres, located, as is Marfa, in the arid, high Chihuahuan desert. The full tour takes four hours – two in the morning and another two after a break for lunch – and viewing the collection requires spending significant amounts of time in the sun outdoors and travelling distances from 0.5 mile to 1.5 miles on terrain that often includes uneven, thorny, or rock-covered ground. So, they ask you to dress comfortably and sensibly for the climate and landscape and open-toed shoes and sandals are not recommended ! Chinati can be challenging for people who have difficulty walking, so my travelling companion was unable to undertake even the shorter Selections tour.

At the centre of the Chinati Foundation’s permanent collection are the 100 untitled works in mill aluminum by Judd which he installed in two former artillery sheds and this is where Valerie took us to commence the tour.

The size and scale of the buildings determined the nature of the installation, and Judd adapted the buildings specifically for this purpose. He replaced derelict garage doors with long walls of continuous squared and quartered windows which flood the spaces with light and he also added a vaulted roof in galvanized iron on top of the original flat roof, thus doubling the buildings’ height, with the semi-circular ends of the roof vaults made of glass.

Each of the 100 works has the same outer dimensions – 41 x 51 x 72 inches – although the interior is unique in every piece. The Lippincott Company of Connecticut fabricated the works, which were installed over a four-year period from 1982 through to 1986 with funding for the project provided by the Dia Art Foundation.

In the late 1970s, Judd acquired the former fort, Fort D.A. Russell, and began converting the buildings in order to house permanent large-scale art installations. Originally conceived to include works by himself and his friends, John Chamberlain and Dan Flavin, the museum was later expanded to include works by Carl Andre, Ingolfur Arnarrson, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Ilya Kabakov, Roni Horn, Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, David Rabinowitch, and John Wesley. The museum opened to the public in 1986 as the Chinati Foundation.

Fort D. A. Russell is the name given to the military installation that was operational from 1911 to 1946, its namesake being David Allen Russell, a Civil War general who was killed at the Battle of Opequon in September 1864. In 1911 it was established as Camp Albert, a base for cavalry and air reconnaissance units sent to protect West Texas from Mexican bandits after a raid by Pancho Villa.

The base was expanded and renamed Camp Marfa during World War I and, in the interwar years, it became the headquarters for the Marfa Command, which replaced the Big Bend District. In 1924, a patrol called the Mounted Watchmen was established to deter aliens from crossing the Rio Grande until, in 1930, the base was renamed Fort D. A. Russell. The name had been used on a previous military base in Wyoming but it became available when that post was renamed Fort Francis E. Warren. The base was briefly abandoned during the Great Depression and, in January 1933, the Army closed the post but reactivated it in 1935 as the home base of the Seventy-seventh Field Artillery.

During World War II, the post was expanded and used as an air base, a base for a WAC unit, a training facility for chemical mortar battalions, and a base for troops guarding the US-Mexican border. The Marfa Army Airfield was constructed nearby and was used as a pilot training facility and German prisoners of war were also housed in a camp on the base.

In 1945, shortly after the end of World War II, the fort was closed during America’s demobilization and, in October 1946, it was transferred to the Corps of Engineers. The Texas National Guard assumed control shortly afterward but, in 1949, most of the base’s land was divided up and sold to local citizens.

At the start of the tour you are told not to take any photographs and I must say that, although the temptation was there to whip out the iPhone, this rule seemed to be strictly observed by the group that I was in. In any case, a young man was employed to spend his day incarcerated here as backup to Valerie who later in the tour declared that she was authorised to pounce on any offender who might desecrate any item of work by so much as breathing on it !

I asked a few questions as we went along and was curious about whether insects penetrated the building, as I had seen one fly buzzing in a window where there were gaps in the old, original frames. Apparently they do have problems from time to time and lizards from the desert have got in and, in particular, there was at least one spot of acidic bat shit which had despoiled the surface of one piece. Purity of original surface was paramount for Judd even though he was happy to leave milling marks on some of the surfaces ! But he wouldn’t have been pleased by this violation !

Some of the Aluminium panel joints were not as tight and accurate as some of the others, which were better, and Valerie thought that this might have resulted from the variations in temperature that occurred over time, from very hot to cold. The Foundation has to undertake conservation which is costly, especially now that they have to generate their own funds as the DIA money stopped when Judd chose to sever that relationship.

Judd wrote an essay about the Artillery Sheds which first appeared in “Donald Judd, Architektur”, Westfälischen Kunstverein Münster, 1989, and which I found useful in considering the works –

“The Chinati Foundation is primarily Fort D. A. Russell, but also includes the building for John Chamberlain’s work in the center of Marfa and two square miles of land on the Rio Grande for a very large work of mine made of adobe. Most of Fort Russell was a ruin. Other than the two artillery sheds and later the Arena, I was against buying it. It had been an army base, which is not so good. Most buildings were without roofs, there was trash everywhere and the land was damaged. Some of the barracks had been turned into kitsch apartments with compatible landscaping. Military landscape overlain with a landscape of consumer kitsch is hard to defeat. At any rate the artillery sheds were concrete and solid, although they leaked.

The buildings, purchased in ’79, and the works of art that they contain were planned together as much as possible. The size and nature of the buildings were given. This determined the size and the scale of the works. This then determined that there be continuous windows and the size of their divisions. The windows replaced the derelict garage doors closing the long sides. A sub-division of nine parts, for example, would be too complicated in itself and as bars in front of the works of art, smaller to larger inside, rather than larger outside as part of the facade to smaller inside as part of the sub-division of the interior. The windows are quartered and are made of clear anodized extruded aluminum channel and re-enforced glass. One window of each building slides open, which isn’t enough, but the sliding windows were much more expensive. The long parallel planes of the glass facade enclose a long flat space containing the long rows of pieces. The given axis of a building is through its length, but the main axis is through the wide glass facade, through the wide shallow space inside and through the other glass facade. Instead of being long buildings, they become wide and shallow buildings, facing at right angles to their length.

As I mentioned, the flat roofs leaked. In ’84 the one hundred mill aluminum pieces in the two buildings were nearly complete and needed greater protection. Since patching the flat roof had been futile, and since insulation was needed, and for architecture, I planned a second roof. In Valentine nearby, thirty miles, there was a large metal storage building, one curve from the ground to the ground, with very deep and broad corrugations, obviously structure itself. Similar vaults were built as the roofs of the two artillery sheds. The height of the curve of the vault is the same as the height of the building. Each building became twice as high, with one long rectangular space below, and one long circular space above. The ends of the vaults were meant to be glass, but were temporarily covered with corrugated iron. With the ends open, the enclosed lengthwise volume is tremendous. This dark and voluminous lengthwise axis is above and congruent with the flat, broad, glass, crosswise axis. The buildings need some furniture and some use for the small enclosed space that is within each one”.

We moved on to another block which had “Chinati Thirteener”, designed by Carl Andre for the courtyard of Chinati’s temporary gallery. It consists of 13 strips of hot-rolled steel plates, each 12 x 36 inches, laid out in equal distances on a surface of gravel. These lines mark the rectangular area in loose relation to the vertical posts running along the porch. An interesting aspect is the alteration of smooth steel surfaces and rough gravel and the distinction between them has been enhanced over time, as the steel plates have entirely rusted and show an even greater contrast to the pebbles than they originally did. The piece was first installed at Chinati in 2010 and is the newest addition to Chinati’s permanent collection.

In a couple of places the plates overlapped so it seemed not to have been perfectly designed for the space but some in the group were happy to be allowed to walk on the plates. I suggested that there is a division between those of us, the OCD people, who have a rage to see the work retained in order, and the others who want to participate, as Andre himself encouraged, in walking on the work. I mentioned an Andre piece in Tate Modern that was disrupted and all over the floor when I last saw it, a real disruption of the original, planned, ordered form. But, I guess that Carl could live with that.

Inside this block there were some of Judd’s prints, some lithographs and woodcuts and some basic screenprints. This exhibition, “Donald Judd : Prints”, is the first comprehensive exhibition of his prints in an American museum, the works, 70 in all, dating from 1960 to 1993.

In particular there was a series of lithographs that had been completed by Valerie’s husband, Robert, after Judd’s death, printed, she told us, on some rather inferior quality paper that Judd had acquired while on a trip in the Far East. Valerie told us about Judd’s preference for using oil paint colour for his cadmium red which had caused Robert some difficulties. Judd’s sense of colour didn’t seem to me to be particularly subtle or developed but later, back in the entrance office, I came across a book on Josef Albers, whom Judd had written articles about and read Albers’s brief riposte to what he perceived as a criticism of his theories by Judd.

Judd assigned Albers a prime place in his search for a way past Abstract Expressionism, particularly for the German artist’s use of colour and of rectangular variants, which Judd explored in his final series of works, as he thought that Albers had overturned the traditional conception that colour is either a harmoniously composed totality or symbolically allusive. Judd, likewise, rejected traditional colour usage in his wall pieces, stressing instead their self-reflexivity and “uncanny materiality.”

Judd began as a painter but, in 1960, he moved away from the figurative tradition and started to develop his own characteristic, abstract paintings that were, in turn, superseded by three-dimensional objects a few years later. The prints in this exhibition followed that development and echoed concerns of both the paintings and the objects.

There are two particularly active phases of note – the early sixties – represented in the exhibition by eight prints in the central wing – and the period between the mid-eighties and the artist’s death in 1994. In the first years, the prints were conceived as single sheets, but by the late 1960s, most of them were done in series – typically 10 or more sheets – and occasionally as pairs. Such sequences made it possible to elaborate on ideas such as the division of the pictorial space, for example, of the rectangle of the sheet of paper.

The curved lines of the first prints, circa 1960, are close to Judd’s paintings in that the paint is applied thickly – in some cases, also on the back and front – evoking the paintings’ rough and palpable surfaces. The prints also show Judd’s interest in straight lines that regularly divide the pictorial space. Space and spacing became relevant concerns during these years and remained at the core of Judd’s entire work through the rest of his life.

The second of Judd’s notable printmaking periods began in 1986 and these works can be considered analogous to Judd’s three-dimensional objects in that an inner volume and outer frame are each distinguished and transferred onto flat paper. This motive remains prevalent and becomes varied by proportional divisions – halves, thirds, fourths and so on – along with horizontal and vertical divisions of increasingly complex line systems and colour schemes. Thinner and thicker lines make grids of narrower and wider distances and of similar or contrasting colours in relation to the underlying base. The possibilities are numerous and demonstrate the rich potential of such few elements when they become combined. Judd’s preferred medium was woodcut, which he used right from the beginning – all of the prints are woodcut, except a pair of lithographs and a set of screen prints.

Valerie explained the technical rôle that Robert Arber had played in the execution of these works and it was clear that he had carried out the routing of the wood in the large areas of the prints.

The exhibition also included a wall-work consisting of two recesses in green Plexiglass and various pieces of furniture which exemplified the closeness of Judd’s formulations across different media.